Picking a name for a space balloon should be relatively easy. You can always retread a NASA mission name that was particularly monumental (Apollo for example). You could always name it after an 80’s hair metal band: Space Balloon Dokken; Space Balloon Warrant; Space Balloon Slaughter! I find names for anything from bands to space balloons are just better if they happen organically. Anecdotally (and perhaps apocryphally), the name Led Zeppelin came from a conversation between the band and some wise friends who successfully talked them out of calling themselves “The New Yardbirds” by warning that the proposed name would “go over like a Led Zeppelin.” If the name for the greatest rock band of all time came from organic conversation, perhaps it’s a good enough method for naming a space balloon.

Before flying anything in US airspace, it is necessary to contact the FAA to register a flight plan. The logic behind this is simple:

Mid-Air Collisions = Bad

Safe Flying = Good

In that spirit, one of our team members contacted the friendly government agency only to be told that flight plans are not required for aircraft under 10 lbs. While that made significantly less work for our team, it was a bit disconcerting. What if our little balloon hit a passenger jet? Or anything else? Remember our equation: Mid-Air Collision = Bad! After some discussion and lots of joking we decided to plot a route to the Mexican border (just in case), risk-up, and proceed with the project. We also decided the joke of the project would be the name: “Space Balloon Don’t Hit a Jet”.

The build followed numerous online tutorials (a simple Google search will yield lots of hits) and essentially consisted of a giant weather balloon, a model rocket parachute, a red-neck chic Styrofoam cooler, a SPOT GPS tracker, a couple of cameras, an embedded development board with a barometric altimeter hacked onto it, aluminum foil, glove warmers and Styrofoam peanuts. The particular still camera chosen required a firmware modification in order to continuously shoot photos at 30 second intervals. Good thing one of our team members happened to be an embedded firmware ninja–code change executed, new firmware flashed to camera, voila!

At a project meeting, a concern was raised regarding flight time and the battery life of the cameras. Using our handy-dandy balloon calculator web app, (http://weather.uwyo.edu/polar/balloon_traj.html) we determined that our balloon flight time would be around 140 minutes. Armed with that information we fully charged our video and still cameras and let them run until they both ran out of batteries. The good news: both camera batteries would survive until apogee was reached. The bad news: battery survival until landing was not likely.

The final touch in our effort to “Not Hit a Jet” was increasing the visibility of our payload<= fancy word for Styrofoam cooler. The team decided that spray painting the cooler orange would do wonders for visibility. But how much good would orange paint do to alert the captain of a passenger jet to impending doom? Lucky for our team, the author is an RF systems and radar design ninja. The simple solution was to fashion some radar corner reflectors out of aluminum foil then duct tape them to the side of the cooler. With the reflectors installed, our little balloon would look so big to an aircraft radar system that they might mistake it for a reincarnation of the Hindenburg. Safety achieved!

The night before the launch the weather was terrible. The wind was over 15 knots, rain was coming down and the cloud ceiling was less than ten thousand feet. A quick exchange of text messages and the decision was made to wake up at 4:00AM and do a quick weather re-check.

By 4:00AM the weather had cleared. The moon and stars were out and the wind was virtually non-existent. The storm had blown itself out overnight and it was looking like a perfect day for launch. Making a quick check of our balloon calculator, it was determined that the ideal place to launch in order to have our balloon land just south of the Salton Sea and just north of the Mexican border was a wind farm just north of Palm Springs off of the I-10 freeway. Go Time!

While launching a balloon in the middle of a wind farm might seem like a bad idea, on a calm day the turbines are not turning and the airspace overhead is clear. When we arrived, we found a perfect launch site and setup base camp. The payload team eagerly got to work installing cameras and prepping the “payload”. The balloon team began unpacking the balloon and helium cylinder. As the balloon was nearing a filled state, batteries were installed and cameras were started. Once the cameras were turned on, the team worked with a sense of urgency. From that point forward, every minute we spent on the ground wearing out batteries was a minute we would not get footage of SPACE!

The cooler lid was firmly placed on the payload cooler and duct taped in position. The cooler was then attached to the balloon and we were ready to launch. The balloon team began slowly letting the balloon ascend by letting out the cord while the payload team firmly held the cooler. When the balloon was at full height and there was no more slack between the balloon and the cooler, it was time to launch. The count down…5…4…3…2…1. The balloon sped into the blue sky with the orange cooler below it. There were shouts and exclamations all around. Then the waiting.

We received telemetry messages from the GPS tracker every 10 minutes, however there was a catch. In order to prevent terrorists, enemy combatants, etc. from using GPS to guide bombs, commercial GPS trackers stop working above ~30k feet. Not ideal for a space balloon but the alternative–getting a military tracker–was not realistic. After about 20 minutes, we stopped getting updates from our balloon. This meant we had reached 30k feet. It also meant we would hear nothing from Space Balloon Don’t Hit a Jet until it was on its way down more than two hours later.

After the brief celebration and relief at a successful launch, tension returned to the team. Based on our calculations and the weather report, we expected the balloon to be landing in just over two hours in the Coachella Valley between the Salton Sea and the Mexican border. The smart thing to do was to start driving while monitoring the laptop for GPS updates from our balloon.

We piled in the car and started heading south down the Coachella Valley past Palm Springs toward the Salton Sea. While the mid-century modern architecture of Palm Springs whizzed by with all of its Space Age, Jetsons charm, the mood in the car bounced between guarded optimism and outright worry as we waited to see if our space dreams would come true.

As we neared the Salton Sea time was up. According to our calculations, the payload should be descending under parachute below 30k feet. This meant a GPS update from our tracker should be appearing on the laptop screen any minute. It was at that point we all could relate to the scenes of mission control room operators at JPL or Johnson Space Center nervously awaiting contact with their craft. A minute went by, then two, then it was there on the screen: a latitude, a longitude, an elevation and a sigh of relief! Cheers burst out in the car!

According to the plot on Google Maps, the payload was just north of the Salton Sea at 20k feet traveling south…south toward the Salton Sea. No one wanted to say it, but at this rate there was a chance the payload would end up in the water. This was an eventuality we had not planned for. The Styrofoam would float but would the cameras be destroyed? More importantly, would the SD cards holding the images and video be destroyed if they were exposed to the salty water?

Another update…10k feet…over the north west corner of the Salton Sea…traveling west. It was going to be close. We pulled over to the side of the road next to the Salton Sea and scanned the cobalt blue sky for signs of our orange payload under parachute. After a few false alarms, another update came in. The payload was on dry land about a mile west of the north end of the Salton Sea. Relief!

We punched the latitude / longitude coordinates into our smartphones and awaited directions from Google’s servers. The Google Maps app replied with directions to only the nearest roadway to our craft. Worthless. So filled with excitement were we however, we decided we would just wander out into the desert and find it. After all, how hard could be to find an obnoxiously orange Styrofoam cooler in a large desert? Answer: hard!

After walking through the desert for thirty minutes hoping to stumble across the payload with no luck, the team was filled frustration and running low on water. We regrouped. Solutions were tossed out along with a little blame. After all, it was the author’s responsibility for developing the system to locate the craft once on the ground. I had failed the team on this part of the mission design. If one lives by Google, one dies by Google–Google had let me down. We were just so tantalizingly close to a successful mission it was painful. If only there was a way to get the raw output of the phone’s GPS to display on the screen. We had the payload coordinates, all we needed were our own.

Then the solution came clear. It was a solution that any self-respecting person who came of age in the smartphone era would have found obvious. Download an app! Of course! “Lost your space balloon? There’s an app for that.” A quick browse through the Android Market and a free app was found that promised everything we needed–it even had four stars to boot! Download complete and GPS coordinates displaying, we determined the required heading. We started walking, then trotting, then running full speed.

“I SEE IT!” The sprint was on. The craft was soon surrounded by our team and victorious photos were taken. But the real moment of victory would only occur if the SD cards in the cameras contained beautiful images.

Back at the car, our trusty laptop had run out of batteries. It seemed that the obstacles wouldn’t stop coming. Thankfully, no self-respecting engineer goes to battle without a 120 Volt AC inverter in his pocket (or glove box). Out came the inverter, in plugged the laptop and up booted Windows.

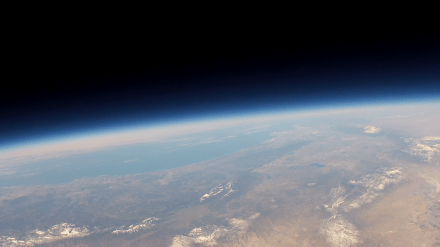

As the images appeared on the screen the excited team fell silent. A team that couldn’t stop talking all day was finally left speechless. Earth, our home, below and the inky black nothingness of space above. Minutes of video played with the team wrapped in awe. Finally, the words “It’s beautiful,” broke the silence. Then cheers and hugs broke out all around.

The mission to the edge of space was a success. The mood was jubilant and victory beer was consumed by all. The Styrofoam cooler was even intact enough for another round trip off the planet. A second trip however, will need to wait for a new name.

Photo from Apogee:

Plots of Data Taken by Embedded Board and Sensors: